“And even the Jordan River has bodies floatin'” refers to the War over Water.

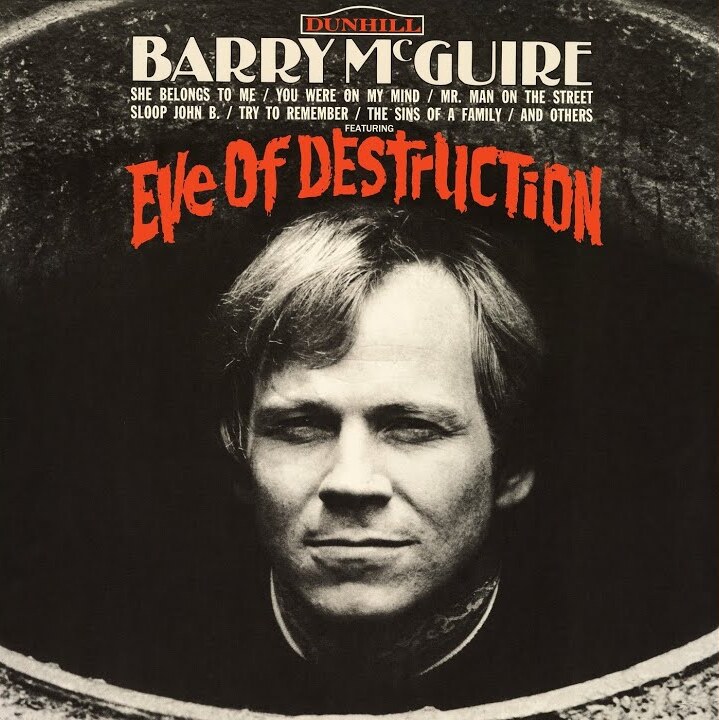

McGuire’s gravelly voice lent the track a sense of urgency, speaking directly to a youth growing increasingly disillusioned with the Vietnam War, racial inequality, and environmental degradation. The opening lines, “The eastern world, it is explodin’,” set the tone for a song that would unapologetically confront the issues of its time. The line, “You’re old enough to kill, but not for votin’,” encapsulated the frustration of many who felt trapped between the responsibilities of adulthood and the lack of agency to change their world.

“You’re old enough to kill, but not for votin'” refers to the United States law requiring registration for the draft at age 18. The minimum voting age in most states was 21 until the ratification of the Twenty-sixth Amendment in 1971.

“Eve Of Destruction” quickly climbed the charts, reaching number one on the Billboard Hot 100. Its controversial message divided audiences—some embraced it as a call for change, while others rejected it for being too stark and pessimistic. Many radio stations banned the song, but this only fueled its popularity. For those advocating for civil rights, peace, and environmental reform, it became an anthem that voiced their discontent.

“If the button is pushed, there’s no runnin’ away.” refers to mutual assured destruction.

More than just a hit, “Eve Of Destruction” arrived at a pivotal moment in history. The 1960s were marked by civil rights marches, anti-war demonstrations, and a growing generational divide. McGuire’s song wasn’t just a reflection of these times; it was a rallying cry that galvanized a movement. As young people filled the streets in protest, music became more than entertainment—it became a tool of resistance, a way to unite and express collective frustration.

The song’s mention of Selma, Alabama, refers to the Selma to Montgomery marches in March 1965. The Jan and Dean version substitutes “Watts, California” in the lyrics, in apparent reference to the Watts riots that occurred in Los Angeles later in 1965.

The song’s blunt, unfiltered message resonated with a generation caught in the crossfire of ideological battles. From the escalating Vietnam War to the nuclear arms race, “Eve Of Destruction” challenged listeners to confront uncomfortable truths about the world they lived in. It underscored the precariousness of life in the atomic age, while also touching on race relations, making it a multi-faceted critique of the times.

“You may leave here for four days in space, but when you return it’s the same old place” refers to the June 1965 mission of Gemini 4, which lasted just over four days.

Despite its critics, who argued that the song was too divisive or pessimistic, “Eve Of Destruction” solidified its place in history. It reflected the frustrations of a generation and, perhaps more importantly, showcased the power of music to not only document history but to inspire change. Over fifty years later, the song stands as a reminder of music’s ability to challenge the status quo and give voice to those calling for justice.

The legacy of “Eve Of Destruction” endures. It remains one of the definitive protest songs of the 1960s, a powerful testament to the role of music in shaping and reflecting social movements. In a world where the issues it addressed are still relevant, the song continues to resonate, reminding us of the potential for art to drive meaningful change.

“Hate your next door neighbor, but don’t forget to say grace” refers to simple hypocrisy, according to Sloan.

Despite its detractors, who claimed the song was too pessimistic or divisive, “Eve Of Destruction” solidified its place in history as a protest anthem that reflected the frustrations of a generation. It remains a powerful reminder of music’s ability to not only document history, but to inspire change.

Any details available on when Barry McGuire was arrested in Stockton, California at the Civic center for singing Eve of destruction? Seems he was opening act for Jefferson airplane. 1965 or 1966.

There’s no real expanding ideas or explanation to the verses mentioned. for example, the reference to the Gemini 4 mission likely showed the frustation in that soldiers were undergoing a much greater toll, without the same acknowledgement, but this isn’t mentioned at all in an article expected to deepen readers’ understanding of the underlying themes and motivating factors.